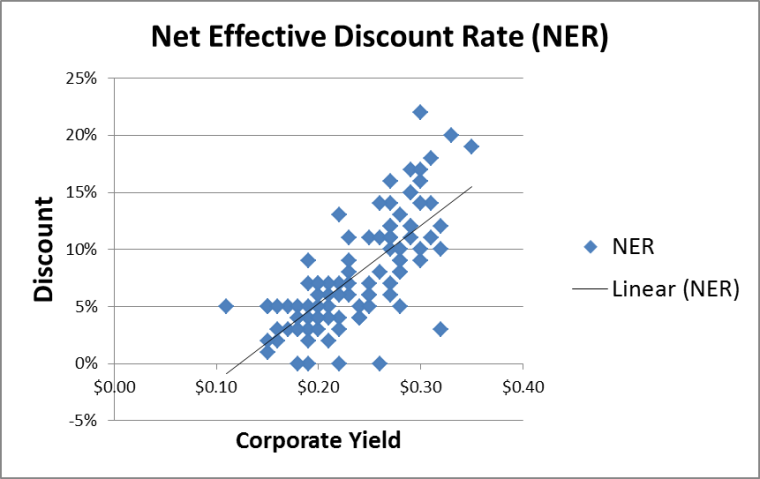

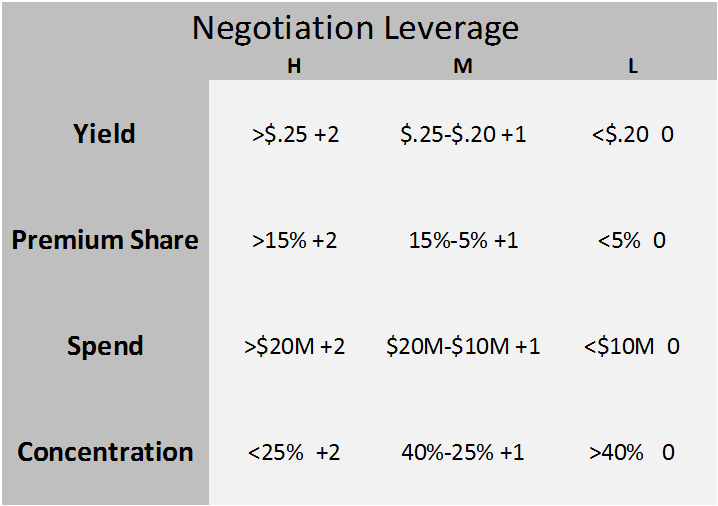

Start with yield

Revenue yield is a terrific measurement to compare airlines, corporate travel programs, prices, cost structures, and traveler behavior. It’s widely known that two travelers on the same flight may have very different profit or loss profiles. The first passenger might generate 7¢ per mile, while the second spends over $1.00 per mile on the same flight. Still another passenger who shelled out 9¢ per mile on a long-haul in coach, might have contributed to an operating loss for the same carrier when they connected to a 200 mile flight on a regional jet that needs to generate 40¢ per mile to break even. It’s important to avoid comparing the margins against each other, but instead, travel managers and analysts should group flights by trip distance, cabin choice, advance purchase and price paid to develop skills to separate good deals from expensive ones.

Automobile financials and operating statistics are similar to airlines on a smaller scale. They provide a framework for readers who are less familiar with airline data. Edmunds.com hosts a terrific tool that allows you to determine the “True Cost to Own” any vehicle with specific options you select. This feature provides a breakdown of the factors used to calculate ownership costs including: Depreciation, Taxes and Fees, Financing, Fuel, Insurance, Maintenance and Repairs. When you know the cost over a five year period, you can divide that by the number of miles you drive to find the Cost Per Mile. Edmunds’ formula for a top seller reveals that a 2012 Camry XLE will cost about $44,000 to own for five years and drive 75,000 miles. This means the owner will spend 59¢ per mile and this yield is an apples to apples comparison to the cost to fly.

The Edmunds values make sense especially when you compare them to the IRS mileage reimbursement rate currently 55.5¢ per mile.

Let’s expand the personal auto example and add airline-like overhead. Consider the revenue per mile Yellow Taxi generates from customers in Chicago, Illinois. They use a two-part pricing model that combines an “access fee” $3.25 for the first 1/9th mile, with 20¢ for each 1/9th mile after that (ignore the other add-ons for this). A one mile ride costs $4.85, but that drops down to $2.41 per mile by the fifth mile. We already know that 55¢ is a reasonable estimate for Yellow Taxi’s operating cost, but that excludes a taxi license, communications expenses and the driver’s wages – it’s not a stretch to imagine that a taxi company’s expenses could top $1.00 per mile and double that when you consider mileage without a passenger. Drivers and taxi permits are major expenses that dramatically increase the cost to operate a taxi company in any city and “repositioning” costs are not insignificant and analogous to airlines’ costs for terminals and flight crews. Airlines can carry passengers far below the $2.00 per mile Taxi’s need, and they do it a thousand percent faster.

A refresher about the cost of personal transportation is a great segue into the world of airline finance and passenger yields. I’ve written about Form 41 data before, here, but want to point out a few excellent resources for airline data – the Global Airline Industry Program at MIT and their Airline Data Project. Additionally, Bill Swelbar’s blog, Swelblog, houses his opinions and analysis of current industry trends. Those sites along with select annual reports provided the data for my analysis.

As fuel prices continue to have an outsized impact on airline operating expenses it’s important to understand what’s going on behind the scenes to make predictions about how prices may change in the future. I modeled an airline’s cost structure first; I’ll describe a few assumptions through a discussion about aircraft operations that allowed me to calculate the variable and fully allocated costs of each seat mile.

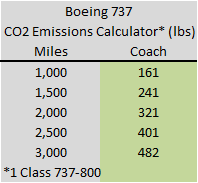

Begin with a short haul flight between Boston and LaGuardia, a 186 mile flight scheduled to operate over 113 minutes – only 31 minutes in the air. The balance of that time is used to taxi, park, load and unload. Short flights are burdened with higher costs for low aircraft utilization, gate expenses, ground handling and other costs that cannot be sprayed very far when you only have 186 miles to generate revenue. A fifty seat regional jet would create 9,300 Available Seat Miles. The flight will consume more than 230 gallons of Jet A priced at $2.80 per gallon and the crew salaries and benefits will be about $437. That gives us a variable cost near 11¢ per seat mile, while adding ownership costs, maintenance expenses, landing fees and other SG&A drives the cost per available seat mile up to around 37¢ per mile. The flight needs to generate more than $3,500 to break even.

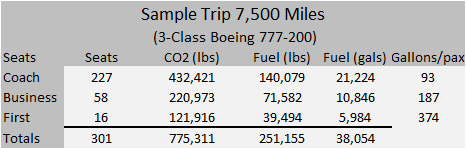

On the other end of this model: Chicago -> Hong Kong, with a three cabin Boeing 777-200 with generous cabin space and 245 passengers. Current fuel prices demand this flight generate more than $290,000 over the 7,800 miles between these two cities. The fuel expense alone is more than $100,000.

Gate time incurs agent expense and airport rent, while taxi time drives full pay for the cabin crew and burns fuel. Wheels-up time is actual flying time (high fuel burn). Block time is literally the sum of minutes the plane isn’t parked with wheel chock blocks in place. Each phase of the commercial operation has a different expense profile – the key takeaway is that flying is only a fraction of the cost. Click on the table for a detailed view.

Now that you know something about the time demands based on stage length, you can combine that with expense ratios to predict how much revenue an airline must generate for each seat. Airline expenses are captured in the following categories in predictable ratios starting with fuel expenses (38% of revenue), crew costs (30%), aircraft ownership (10%), maintenance (10%), SG&A (12% – includes airport leases, landing fees, and other selling, general and administrative). Fuel, Maintenance and Crew costs are cash expenses an airline can avoid when they reduce their schedules, but rent, leases, ownership and overhead will continue to be paid and those costs will rise in the short term as capacity declines.

Break-even Yield data is available and fare information is easy to find – they can be used to construct a simple excel model to allow “goalseek” and other “what-if” scenario tools to apply simple rules and ratios to predict fares by cabin on a few routes. In the table below Cash Cost is the direct cost of operating the trip including crew salaries and benefits and fuel; VCASM means Variable Cost Per Available Seat Mile, CASM is the fully allocated Cost Per Available Seat Mile, blended CASM is the average Cost Per Available Seat Mile and combines costs for coach and other premium cabin seats.

Predictive pricing models

Since fuel, crews and maintenance account for 70% of airlines’ total passenger revenue (at break-even margins), a leisure fare, marketed directly, is unlikely to sell for less than the variable cost of the seat; variable costs put a floor under the model’s leisure price (consolidator’s frequently have access to fares that just cover the fuel cost). I modeled a few variables to see how this assumption holds up and to determine if a simple model could predict industry pricing.

Divide fares into Leisure, Full Y (full fare coach), then F/J (domestic first, or business class), assume Leisure fares are 150% of the variable cost of fuel and crew expenses, then full Y is 300% of the leisure fare, and First class is double the full Y fare. Those assumptions produce results that look very similar to ticket prices customers are paying. Click for detail.

I changed the previous assumptions to take a deeper look at a three class, long haul trip. Starting with the $295,000 breakeven revenue required from passengers on a 245 seat flight to Hong Kong, I used “goalseek” to find the coach ticket price required if you assume Business Class is three times more than coach, and First Class is three times more than Business Class? The result is below.

Business Class yield stands out – it’s very low compared to what most corporations are paying. Few customers actually pay 77¢ per mile in First Class, and a number of Coach passengers have a better price than shown above – that puts the burden squarely on the shoulders of the bread-and-butter Business Class travelers to make up revenue deficits in other cabins.

This back of the envelope analysis suggests that airlines that operate two-cabin aircraft on International routes actually have enhanced pricing power vs. airlines that operate three cabins. Two-cabin aircraft can dedicate more floorspace to business class and offer all travelers a price point below their three-class competition, while generating higher average revenue. Additionally, more business class seats allow an airline greater flexibility to upgrade coach customers and eliminate expectations that business class customers will be upgraded. Furthermore many airlines use the upgrade waterfall to eliminate overbookings in Coach by closing business class before it sells out, but First remains available. They protect oversales by moving travelers from business to first, and from coach to business. This reduces their First Class revenue and creates disappointment for top-tier, premium travelers when the waterfall doesn’t work out for them.

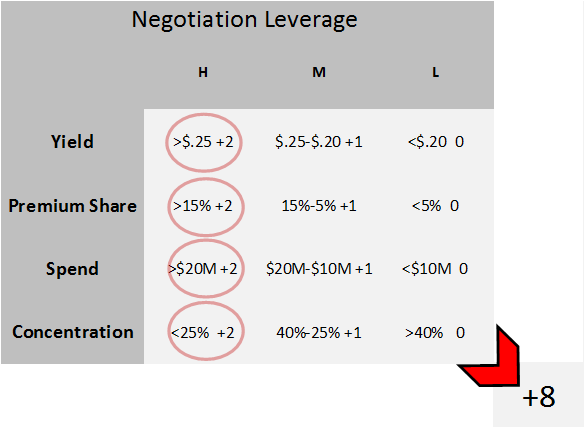

Both models offer you a framework to bin ticket prices by distance and cabin to help you develop your own cost ratios. That information can become the basis for a deeper analysis on your travelers’ buying patterns and will help uncover ways you can change behavior to drive cost savings and negotiate with suppliers.

For more articles about airline operating costs check out: The Secret Behind Airline Fuel Surcharges.